Learn how to run a basic simulation study in R

You probably know that statistical and machine learning methods are are based on a lot of math. So. much. math. For example, we can prove mathematically that OLS estimates \(\hat\beta\) - provided all of the Gauss-Markov assumptions are met - will in the long run converge to the true population parameters \(\beta\).

But what if you do not want to do the math and you still want to test if a given statistical model “works” in a specific situation? Enter simulation studies. In a simulation study, we effectively choose the truth (the so called ground truth) and can test if estimate from our statistical model of choice in the long run converge to that ground truth. We do this by simulating data following from the ground truth we specify, run the model on it, and examine how close the model estimates are to our ground truth. We repeat this process usually thousands of times to get a good idea of how a model behaves “on average” or “in the long run”.

This sounds complicated, but is thankfully very straightforward to implement. If you are like me, soon enough you might find yourself running simulations every time you encounter a new statistical model because you just want to see what the heck it does :)

Basic workflow of a simulation study

The basic workflow of a simulation study is pretty easy.

- First, we simulate our data given a ground truth using a random number simulator.

- Second, run the models we are interested in, on the data we generated in step 1 and store the parameters we are interested in (e.g., regression coefficients, p-values, accuracy…)

- Third, we repeat this a large number of times (say, 10.000 times).

This is it.

A toy example: linear regression vs. t-test.

Suppose we are interested in testing who makes more money: data scientist or data engineers. But we are unsure whether we should use a linear regression or an independent sample t-test. We have a hunch that we should use linear regression. In other words: we want to test if a t-test just as good as recovering the ground truth than a linear regression.

Defining the data

For this example, let’s suppose that we want to simulate data based on the following equation:

\[income = 50000 + 10000 * data engineer + e(\mu=1, \sigma=0)\]In other words, we assume that the outcome (income) is defined as a linear combination of the intercept term (50), 10 \(\*\) data engineer, and normally distributed error term. This ground truth can be interpreted in the following ways: data scientists on average make 50k a year, and data engineers make 10k more than data scientists. Why do we add an error term here? Several reasons, but the main one is that simulations are supposed to approximate “real life”, and in real life there’s always some part of the variation of the outcome we can’t explain due to completely random processes.

We translate this ground truth into the following R code:

make_data = function(sample_size = 10000,

intercept = 50,

beta_1 = 10) {

data_engineer <- rbinom(n = sample_size, size = 1, prob = 0.5)

income <- intercept + beta_1 * data_engineer + rnorm(n=sample_size)

data.frame(income, data_engineer)}

rbinom here is used to randomly generate a dummy variable, with the probability of an observation being 0 (=data scientist) or 1 (=data engineer) being .5. This does not mean that in every single data set we use there will be “50% data engineers” and “50% data scientists” (there values might be 51% and 49%), but that this is true on average in the long run. rnorm simply draws a random number from the normal distribution, and simulates our error term.

Running the models

There are many ways of specifying the code for running the models. My preferred way is to do it in a for loop - I’m that basic.

Let’s first define the key parameters of the simulation. nSims defines the number of repetitions (here set to 1000). We specify a random seed using set.seed so that you get the exact same results as me when running this simulation. We set up two empty containers (linearreg and ttest) to store our model estimates.

The simulation itself is executed in the for loop. For every iteration in nSims, we generate a data set using make_data() we defined above, run a linear regression and store its coefficient in linearreg, and run a t-test and store the mean difference in ttest.

Grab a cup of coffee while this is running, it might take a while depending on your computer.

#Set number of simulations

nSims <- 1000

#Set random seed for reproducibility

set.seed(42)

#Set up vectors for storing results

linearreg <- numeric(nSims)

ttest <- numeric(nSims)

#Run the simulation

for(i in 1:nSims){

#Simulate the data

data <- make_data()

#Estimate linear regression and store coefficient

linear <- lm('income ~ data_engineer', data=data)

linearreg[i] <- coef(linear)[2]

#Estimate t-test and store result

t_test <- t.test(income ~ data_engineer, data=data, var.equal=FALSE)

ttest[i] <- (t_test[["estimate"]][["mean in group 1"]]-t_test[["estimate"]][["mean in group 0"]])

}

Examining simulation results

Now that we have our simulation results, it’s time to examine them and draw a conclusion: can we just use a t-test instead of a linear regression when comparing two means (in the specific situation - ground truth - we defined above)?

Let’s first examine the means of all estimates from linearreg and ttest. If the t-test is as good as the linear regression, its mean difference should be extremely close to the linear regression coefficient, given that we simulated so many data sets.

mean(linearreg)

[1] 9.999933

mean(ttest)

[1] 9.999933

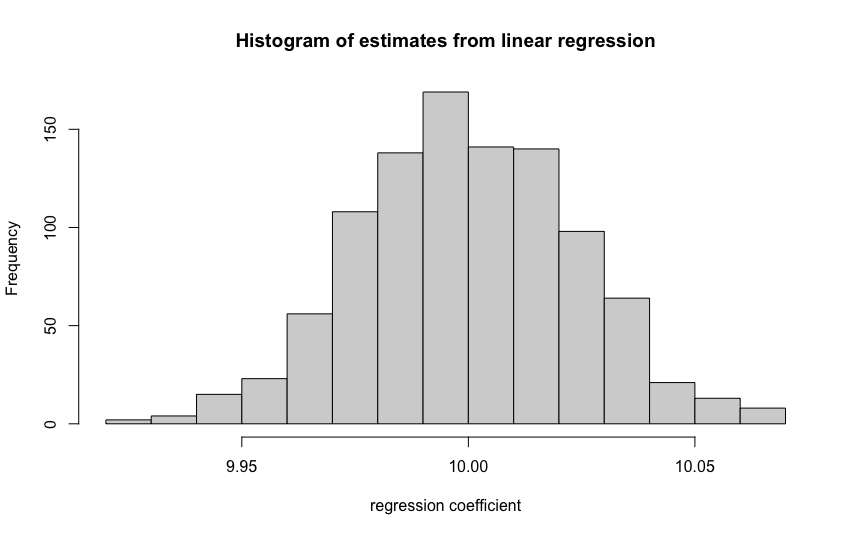

As we see see, the means are identical. How about the histograms of estimates?

hist(linearreg, main="Histogram of estimates from linear regression", xlab=("regression coefficient"))

hist(ttest, main="Histogram of estimates from t-test", xlab=("mean difference"))

They, too, look completely identical and both look like a normal distribution. If we increase the size of nSims, they histogram will eventually look exactly like a normal distribution.

What does this tell us? Yes, if we have a simple model like this (with only an intercept and one dummy variable and normally distributed errors), linear regression and an independent sample t-test recover the exact same mean difference.

Beyond simple examples: what else can you do with simulations?

This was, of course, only a very simple example meant to illustrate the workflow of a simulation study. You can do so many cool things with simulations. For example, you could examine if it makes a difference whether you use a linear probability model or logistic regression under various circumstances (e.g., correlations between variables, range of variables, etc.). Spoiler alert: it does, the LPM is bad. Or you could test what the role of sample sizes is for tests of statistical significance. Spoiler alert: the bigger the sample size, the smaller the average p-value.

If you are more into prediction models, you could test which model yields the highest accuracy/$F_1$: softmax/multinomial logistic regression, KNN, k-means clustering, etc. The possibilities are endless.

In summary

Simulations help us understand how statistical models behave under different circumstances, and which model might be better in situation X. We can do this entirely without math by simply running our model(s) of interest on simulated data a large number of times (e.g., 10,000 times) and calculate and plot summary statistics of the results.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: